When a visitor presses the button, the chime rings in your home and also connects to the Ding app on your smartphone

In recent months the doorbell has been the bane of my existence. A button sits on my doorframe whilst the chime unit in its ugly grey box is plugged into a wall socket ringing out a horrendous tune with no option to turn the volume down.

Ironically, while being home on maternity leave meant I could receive more parcels, I kept missing them as I’d unplugged the doorbell so as not to wake a sleeping infant.

Now, my toddler wanders around flicking off the plug sockets anyway so I’m still missing deliveries and visitors.

But the new Ding doorbell changes all of this with an elegant and contemporary solution consisting of a doorbell button and chime unit that you’d be proud to have on display in your home (and, importantly in my case, be able to keep out of reach of small hands). And although its ‘ding’ can be silenced, the homeowner will still know that someone is outside their front door because an app on their mobile phone will alert them to the fact.

The inspiration for Ding actually came about when its creators – John Nussey and Avril O’Neil, who are business partners and newlyweds – were looking for a doorbell for their own front door when theirs broke.

“We looked on Amazon and went down to B&Q to see what our options were but there was nothing we deemed appropriate. The majority are grey, plastic boxes that make horrible sounds,” says O’Neil. “We came to realise that doorbells are unloved, forgotten objects that don’t work with how we lead our busy lives that we control through our smart phones. We wanted to fix this.”

Three key elements

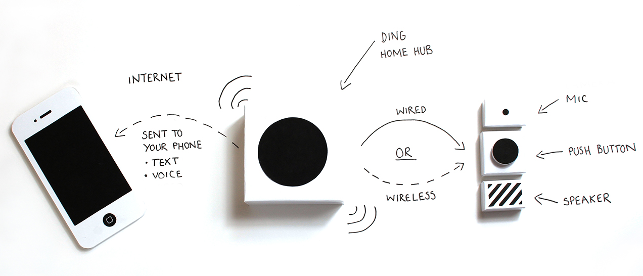

The Ding smart doorbell is made up of three elements.

The first is the button, which is attached to the doorframe and can either be battery powered or hardwired. The second is the chime unit, which is either placed on a surface in the home or mounted to a wall and then paired to the Wi-Fi.

The third is a smartphone app, which displays a push notification when the doorbell button is pushed. The user can then choose to take the call and speak to the person outside their front door whether they are in the house, in the garden, sat in an office, walking the dog or even on a sun lounger on holiday.

There are, of course, as we’re in the age of the Internet of Things, other smart doorbells on the market, but the Ding’s remit is to first and foremost be a doorbell that offers a great user experience wrapped in an appealingly simple design with a few useful features that can be controlled via the app such as setting the kind of chime you want, looking at caller history, or scheduling in some quiet time in the day when the ‘ding’ is diverted to your smartphone.

It’s certainly not an overly techie device with all manner of capabilities. “We wanted to use technology to make a smart device but not a gadget that was all singing and all dancing because that only appeals to one type of user.

Our approach was to create a simple yet elegant solution just like a traditional doorbell but then add useful layers of technology on top,” describes O’Neil.

And you can see how this simple yet smart product would appeal to all manner of users, both young and old. In fact, O’Neil’s grandmother was her inspiration. “My nan has multiple sclerosis and lives in a first floor flat. When the doorbell rings, by the time she has gone down on her stair lift the person might not be there anymore. For me that was massive – making the product work for both new home owners in their late 20’s through to those in their 80’s.”

However, with their design consultancy ONN Studio to run, which they’d set up together three years ago, O’Neil and Nussey had very little spare time to work on personal projects. That was until they came across the Design Council Spark programme.

Launched as a pilot in April 2015, this product innovation fund and support programme was set up by the UK Design Council to give a handful of successful ideas the boost needed to get them to market. “We entered quite flippantly the idea for Ding. Just a general explanation of what it might do on a hunch that we might be onto something.”

Their hunch proved true as Ding was selected as one of eight finalists chosen from a group of 350 applicants to receive £15,000 in funding and they were also invited to attend a fast-track 20 week programme, by the end of which time they’d have developed a prototype.

The finalists would then pitch their prototypes in front of a panel for the chance to be one of three winners to be awarded a slice of the £150,000 prize money.

In order to define exactly what Ding would be, the pair started off the programme by doing research with users.

“An interesting insight was that some didn’t even know where the chime unit was in their home and indeed where the sound was coming from,” says Avril.

“From research it also became clear that people wanted to be connected to their homes even when they were not physically in them and the main way to do this is through a smart phone as most people have it with them all the time.”

The Ding smart doorbell is made up of three parts, a subtle doorbell button for the front door, a doorbell chime that sits in the home and a free smartphone app

Simple is challenging

To inject intelligence into the doorbell it would need some clever technology but as O’Neil stresses, the real challenge for them was to create a simple product that integrates seamlessly into users’ lives.

“The technology was a big thing for us. I think a lot of people see design and technology as being different things but technology is a really creative part of our process.

However, with any technology project, the drive is to get it to do all sorts of amazing things because you can but then you end up with an overly cluttered product.

“Equally, to make something simple is a really difficult challenge too because you have to do a lot of work to keep it simple, which sounds mad,” laughs O’Neil.

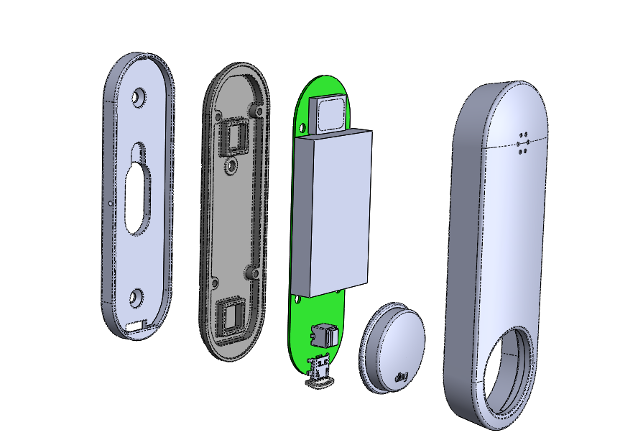

To translate their sketched ideas into 3D models they used Autodesk Fusion 360. This is one of the many tools available to them being residents of Makerversity, a collective workspace Somerset House (see box out below).

O’Neil heartily recommends such a shared space for startups not just because of the facilities it offers but for bringing various ‘makers’ together. “The wonderful thing about Makerversity is that we have been able to tap into and work with a lot of its residents who have skill sets that we don’t,” she comments.

“I think the hardest thing for startups is, because you’re on your own, it can feel quite daunting. But being surrounded by people who are going through the same thing and being able to share experiences really helps.”

A SolidWorks model of the doorbell button

Getting a boost

With the 20 week Spark deadline fast approaching, the pair made dozens of rudimentary prototypes to test their ideas.

They hacked bits of technology together, made card models, used various hand tools, laser cutters and a Makerbot 3D printer until they had refi ned their design to a state they were happy with and then sent the CAD files to a model maker so that they had a model for the Spark panel.

They emerged from the panel as one of the three finalists to win the prize money. With funding in place, to turn their prototype into a marketable product, they decided to grow their team bringing in industrial designers, engineers, developers and marketers.

For O’Neil, it was a relief to bring in some new ‘heads’ to join hers and Nussey’s as it allowed them to focus on other areas of the business. “As a startup you have to do ten billion jobs at once. You have to switch between your finance head, your technical head, marketing head, design head… it’s quite challenging to keep all of those different job roles,” she describes.

“There is so much to juggle and involves so many different skills. But, saying that, we have learnt a great deal. We’ve had to understand all those aspects of our own business rather than relinquishing the responsibility onto others, and that’s really important for a new company.”

To make it a manufacturable consumer product, the design needed to be revised but not just its exterior look and feel but the technology on the inside too. “We started off using a different technology that would require a simcard in every doorbell, which wasn’t appropriate for a mass market product.

We then moved on to develop a Wi-Fi based solution. The doorbell connects to the chime using a local connection (using DECT based technology), this then connects to your home Wi-Fi, which begins a call with your smart phone,” explains O’Neil.

“We have also designed it so that even if your Wi-Fi should go down your doorbell still works. What has been most important to us is that the doorbell works as a doorbell!”

Working with industrial designers from London design consultancy Map, they then revised the doorbell and chime unit to provide the optimum user experience and also design it for manufacture.

“The button changed quite a lot over the course of the design process. In collaboration with Map we created the chime first and its shape then informed what the button would look like,” explains O’Neil.

“What’s interesting is that although this two part system arrives in the packaging together, for the rest of their lives they have completely different homes. The button sits with the exterior architecture on the outside whilst the chime has to fit in with the interior furnishings.

“That was a hard design challenge to get them so that they are a coherent pair but also giving them the proportions they need so they can exist in their different locations. That is why we chose durable materials for the button and a softer fabric for the chime.”

This time Map used its CAD tool SolidWorks to revise the design and like before, many prototypes were produced as they worked through different ideas. “We made so many prototypes but I think that is about responsible design, knowing that you have explored every avenue of a product to arrive at a final conclusion,” says O’Neil.

An early model revealing the designer’s thinking behind the Ding

Finish line approaching

Then, fresh off their honeymoon earlier this summer, Nussey and O’Neil went straight into another startup accelerator programme this time from retail store John Lewis and its investor partner L Marks.

Ding was selected as one of the five startups from 300 applicants to join a 12 week programme at John Lewis HQ to help fast track product growth by offering product validation, mentorship, investment etc. “We received an amazing insight into the retail world, generating understanding and solving problems we may encounter later down the line, so that we’ll be prepared for retail sooner,” says O’Neil.

With the final design ready and a manufacturer lined up, the pair needed a final bit of funding to take them over this last hurdle. Crowdsourcing seemed an obvious choice not least of all because it would allow them to suss out whether there was indeed an interest in this new smart doorbell.

So, on 11 October 2016 the project was launched onto Kickstarter with various goals including the chance to pre-order a Ding for $129. Seven days later it had reached its target goal of $50,000 and as the campaign closed on 10 November 2016, it had raised $111,453.

It’s obviously resonated with people, which O’Neil puts down to its simplicity. “It was a risk keeping it so simple but it seems to be going down rather well,” she says with a relieved smile.

I have to say that I’m looking forward to chucking away my grey box and replacing it with an item that means I’ll never miss the doorbell again.

Making it

Makerversity offers its members — essentially anyone who is in the business of making for a living — studio or desktop space as well as access to digital and traditional machinery and tools.

First established in Somerset House, London, in 2014 and then in Marineterrein, Amsterdam, we talk to one of its co-founders Tom Tobia

The obvious first question is why did you set up Makerversity in the first place?

Our vision was threefold:

• To provide affordable space for the most exciting maker businesses

• To offer learning opportunities to young people in emerging industries – access to careers they wouldn’t know about through school

• To bring making and manufacturing back to the heart of the city

Why did you choose Somerset House as the location?

Because we took an opportunity to develop a derelict space in an incredible location – one that isn’t tied to the trends of East or West London. Somerset House has a neutrality to it and a gravitas that elevates the professions and people we support.

What partners did you get onboard to enable you to do this?

No one to start with – it was our own time and money. Pearson came on board as a learning partner quite early and that enabled us to bootstrap from there. Autodesk weren’t far behind.

What do members get for their money in terms of the space and tools you offer?

They get permanent desk or studio space, access to digital, wood, metal, textiles and electronics workshops, breakout spaces etc. It’s equally important they have access to each other as a community though. This is where our value truly lies – our community spirit and the fact Makerversity is owned and run by creative people means we have a different and more collaborative vibe to most co-working spaces.

What is expected from a Makerversity candidate?

A monthly membership fee is the cost – averaging £300 pcm. We look for diversity of industry, and you either need to be running a business or have an idea to run a business in some sort of emerging practice, and be making something tangible be that physical, digital, edible or even musical.

How do you go about selecting new tools and processes to bring into Makerversity?

With members largely we respond to what they need whenever we can. There are some core machines that always get used like laser cutters but beyond that we’re flexible. It’s not just facilities but also events, workshops and talks.

Tell us about those?We are a community of makers of all kinds – we’re as interested in hosting talks and workshops that bring people into our world as we are anything else. We do a lot with people like The Prince’s Trust in terms of workshops for young people to explore things like product design.

You seem quite passionate about young people and getting them making for instance with your MakerClub. Why do you dedicate so much resource to this?

Opportunities for learning about the jobs of tomorrow are either non existent or expensive. Every young person deserves to find out about how they can achieve their potential even if they don’t go to university. This in particular is interesting in the context of academic vs vocational routes. There are lots of incredible high value ‘nonacademic’ careers out there and we want to help people find them.

makerversity.org

Ding rethinks the humble doorbell

Default