It’s the little things that make big changes in this world; just think where we’d be without nuts, bolts, screws and all the other connectors left over once you’ve built your Ikea wardrobe.

Rendered view of a Rotite lock for a garden hose

Yet for well over 100 years nothing has really changed in how designers and engineers connect one part to another. Until now.

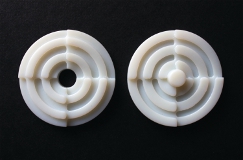

In its simplest form Rotite is a low profile, helicoidal dovetail connector — a geometry that connects with a twist to its partner shape. So far, so jam-jar lid.

However the system is so overwhelmingly customisable, with so many variables, that the possible applications for the technology continue to strike you square in the forehead long after an initial demonstration.

The system provides full surface interlock between opposing connectors resulting in a low profile yet high surface area connection. Geometries of certain connecting profiles can also be identical meaning that objects can be connected without the hassle of A and B, or male and female components.

“All this should have been invented a long time ago, but you would have struggled without technologies such as 3D printing and multi-axis CNC machining,” states Rotite technical director Stuart Burns.

The idea behind the connector came to Burns early one morning, before going into work at Rotite’s sister product design company Ipeology.

He set about creating a quick CAD model, as there was no other way that the idea could be laid out. The file was then sent away to be 3D printed.

“To us 3D printing is ‘get it off the screen and into our hands’ as quickly as possible,” explains Burns while rummaging through several boxes of 3D printed prototypes at his office in Rotite’s Manchester headquarters.

“You can do things on screen, but until you get them in your hands you can’t anticipate certain aspects of how it’s going to interact.” Burns and managing director Damian Vesey used the first 3D printed prototypes to uncover new possibilities.

“The first instance it was a fastener, and then we realised it could be an connector, and then we realised it could be a mechanical coupling as well,” explains Burns.

The next stage was to investigate the possibility of incorporating electronics into the design. “We’re very much hands-on,” he continues.

“We’d get our 3D prints and start drilling holes in them, stick things to them, cut sections out of them, theorise about electronic connectivity.”

This development led to the realisation that Rotite could go beyond the mechanical. “It’s about saving time: connecting parts, closing a seal and connecting electrical components all in one twist.”

Material world

The material for the prototypes was important, with the sliding action and high-resolution essential for testing.

Rotite worked closely with print bureau IPF to utilise its Objet Connex 500 machine to ensure all the specified details were maintained and the finished product had reliable characteristics for testing.

“We’ve always chosen to use the Objet system because of its high print resolution, good surface finish and all that sort of stuff, whereas cheaper things like FDM are just not suitable for us because you have to work on quite high tolerances.”

Getting protected

From the very beginning, licensing the system was the key goal; so securing the Intellectual Property (IP) was critical.

“We used 3D printing as the mechanism for developing the different geometric derivatives, which went perfectly with us developing the intellectual property.

Within a few months the team had set about collating all of its technical drawings to file its first GB patent. A Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) application followed, which was a development of the initial patent that included more derivatives and aspects of functionality.

To top both of these, in both size and stature, was an American patent application, which Burns proudly displays on his desk — the size of a telephone directory compared to the modest dimensions of the other documents.

“One of the beauties of us developing IP is the fact that we’re not necessarily associated with a technology or a company who have got a specific commercial interest.

“It wasn’t developed in conjunction with another project and had to come to market — so there was no rush to commercialise it.”

Reaching out

Now the three-year period of securing the IP is over, the R&D work that the team has done can become more literal as Vesey and Burns push to get companies to license the technology, something their background as product designers has helped greatly with.

It’s all customisable, including the size and material, giving it almost infinite possibilities and variations. It doesn’t have to be flat, it can be conical, domed, or stepped, and can contain integral seals, that when ‘twist-connected’ form an airtight seal.

For electrical connectivity Rotite can go beyond simple on/off functionality.

The twisting motion can also be used to complete circuits in sequence.

“If we think of something like a flat screen TV, we can have a bracket on the wall that has all our contacts in it — all your earths, neutrals, your live, your signal, your HDMI feed.”

“You’d be able to not only physically connect the TV in a really strong way but also sequence that connectivity. “[Twisting the TV onto the bracket] you’d go ‘earth, neutral, live, signal — for people with really sensitive equipment where you can’t have a big spike of electricity going in.”

Staggered start

In the same way as a thread, Rotite can have a number of starts, making it possible to adapt the connector for different types of applications.

For every additional start point required the number of degrees of rotation is reduced.

This feature means Rotite can connect two items together in many ways – from 360, 180, 120, 90 and 45 degrees of rotation, all the way down to a minimal 10 degrees.

“I could make a connector for dangling a light pendant and I could make it with a 10-degree rotation to connect it, but that’s not what you want because the consumer wouldn’t feel safe — they’d want it to go 360 degrees and perhaps ‘click’ at the end, because that’s a real positive user experience,” explains Burns.

“However, if a fireman wanted to grab something in a hurry off a rack with a quick twist of the wrist then that’d be a smaller degree of rotation, because the psychological security is not the issue, it’s functional.”

An education

With the technology in place the next major challenge for Rotite is raising awareness, admits Burns. “If we’re going to get this integrated into society as ‘the most ergonomic, practical fastening system there is’ then we’ve a lot of education to do.

“We want it to be integrated into lots of products; we want it to be standardised so people will be able to look at one and say ‘oh, that’s a size three Rotite’, or whatever,” he says.

Putting the technology into the hands of the design community is key to this strategy and one of the long-term plans is to have Rotite integrated into 3D design software.

Rotite envisages designers being able to generate their own specific part simply by clicking a ‘Rotite Tool’ in the CAD software and selecting a series of boxes (what diameter, the degree of rotation, hermaphroditic or mating, etc).

Although all manner of nuts and bolts are available in design packages, this would be the first to begin its life as a customisable geometry.

By being application-specific and having so many variables Rotite is a designer’s dream connector, fastener, or whatever you want it to be. With the benefits of scalability and the ability to factor in a better user experience, all in a secure, multi-purpose, connector, Rotite could be the little thing that changes the bigger world of design and engineering.

Rotite reinvents connection design

Default