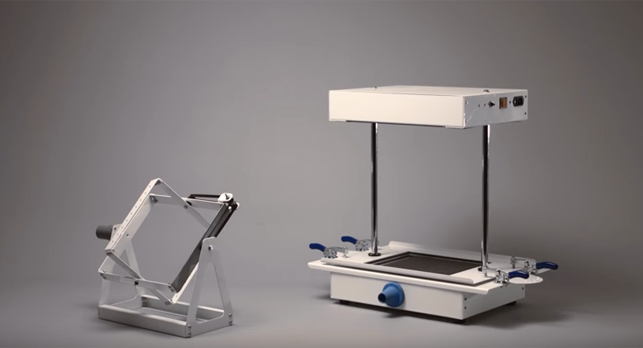

With its nondigital fabrication tools, like its FormBox vacuum moulder, Mayku is hoping making will become a more mainstream activity

A plush café, located in a former royal residence, is not the usual setting for a DEVELOP3D interview, but then again, Mayku is not your typical hardware start-up.

The company is based in Somerset House, an iconic central London landmark. The lavish reception floors of this vast Neoclassical building overlooking the Thames give little hint to what lies beneath: an expansive basement level that plays host to a pioneering community of over 60 maker businesses within its hive of corridors, vaults and old storage rooms. These are coordinated by the organisation, Makerversity.

Opened in 2014 with the goal of providing such businesses with affordable space, tools and workshop facilities, it’s an oasis for product designers in the heart of one of the world’s most expensive cities.

The scheme has continued to expand, and now offers opportunities for collaborations, projects and even seed funding — more of which later.

Back above stairs, Mayku co-founder Ben Redford explains how his company found a home in the building. In his former role as a digital designer for a creative agency, he says, he was responsible for building a number of physical products, a process that got him hooked on making.

His idea for a miniature projector, which shines Instagram snaps copied to physical film onto surfaces, raised $90,000 on Kickstarter. Its development journey took him on a factory tour of China to find PCB and injection moulding suppliers, but also introduced him to a wide range of industrial manufacturing technologies.

“Finding myself in China, I realised that a lot of the machines that are used out there could potentially be miniaturised – not necessarily as powerfully or as effectively as the ones you get in factories, but to a point where the average consumer could understand the process,” he explains.

His idea was that scaled-down versions of rotomoulders (for making single-part canoes and oil barrels) and vacuum formers (for creating packaging) could be good entry-level machines for consumers and still adaptable for more experienced makers.

“If you’re making ten things, but you want to put them in a blister pack, so they look professional [and] so you can sell them at a craft stall, but not just on a cardboard backing… that’s a really hard thing to do. So we thought it’d be a really interesting thing to explore.”

Levelling up

The designs have taken industrial machines and stripped them down into as few components as possible

On his return from China, Redford quit his day job, ensured the stability of his miniature projector business, and started to build models of the machines he’d seen in Chinese factories.

“I come from a digital background, so my process is similar to making websites: I’ll build something shoddy out of glue and sticks to see if it works, and if it works, I’ll level it up a bit,” he says.

“[With] lot of the early prototypes, I wouldn’t even go into 3D CAD until I’d knocked something up on Illustrator, laser cut it, formed it out of those parts, and then [I’d] move into 3D CAD as soon as I knew it would function.”

Initial wooden models of a miniature rotomoulder were enough to encourage him to pursue the idea of developing a full family of miniaturised maker machines, and through a colleague at his previous job, Redford met with Makerversity for the first time.

He was provided with a free hot-desking space for the first three months, giving him time to develop his idea. Through Makerversity, the next step was to apply to the Design Council Spark Fund for financial backing.

A successful pitch saw the idea receive seed capital, and Mayku co-founder Alex Smilansky join the team. The startup then moved into a Makerversity vault space, where the development of their first machines has progressed.

When we meet, the Mayku team is awaiting the arrival from suppliers of iteration five of the FormBox, a desktop vacuum moulder.

The FormBox will be shipped as a completed product, beginning with a Kickstarter campaign. A desktop rotomoulder, christened RotoBox, will be shipped as a beta, with Mayku looking for feedback from designers and modelmakers to aid its development.

“We want to get making stuff more mainstream,” explains Redford. “We think it’s good to start with a nondigital process, because it’s more of an ‘entry-level drug’ for consumers.

“But these are our first two machines and we have a whole lot of other machines in the works, and there’ll be a slow development into digital.”

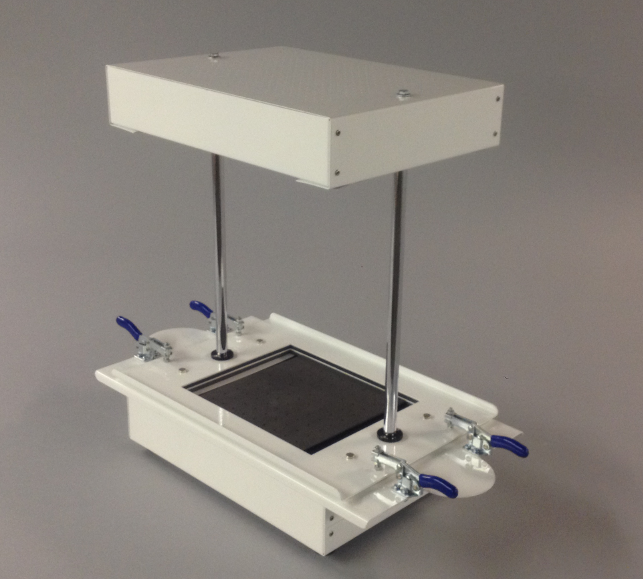

The FormBox vacuum moulder will be released as a completed product, with the final design having a smaller footprint than even this iteratio

New audiences

The target market is clear: the launch products will be available and easy for anyone to use and can be used in conjunction with digital products like 3D printers and laser cutters.

Instead of 3D printing ten simple-shape parts, which might take 100 hours, a user could print one part in ten hours, vac-form it in minutes and produce casts much cheaper and faster in a wide range of materials.

Machine cost and size will play an important part. As Redford explains, most schools now have vac forming on their curricula, but the cheapest machine costs around £1,600 – a barrier for classrooms tight on budget, not to mention space.

“Leatherwork, pottery, all those crafts have one thing in common: they’re really accessible, easy to go and learn how to do. 3D printing has a high barrier to entry: you have to know CAD,” he says.

A miniaturised rotomoulding machine, the RotoBox can help churn out parts faster than simply 3D printing them