The rise of the digital twin continues apace, but is it really anything new? Al Dean has been pondering on the real benefits that this much-hyped trend might actually deliver and how far off they still might be

The phrase ‘digital twin’ is one of those sweet nuggets of corporate speak that has become ingrained in the product development and manufacturing technology industry in recent years. While its origins date back to the turn of this new century, it didn’t really become popular until the mid-2010s. Today, however, it seems you can’t browse any technology company’s website without stumbling across it.

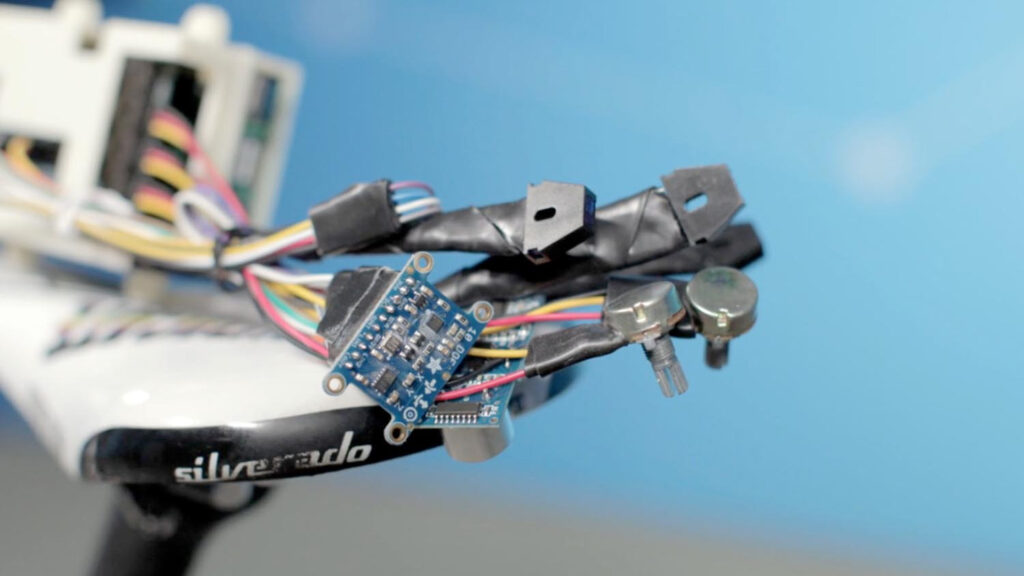

So, what does it mean? There are definitions aplenty, depending on who you ask. To my mind, it refers to the goal of connecting a rich product data model with a physical counterpart, typically using low-cost sensors, Internet of Things (IoT) technology and some nifty software for both data collection and interpretation.

Ask someone else, however, and you may find it applied to a simulation model (no, that’s just a simulation model) or a digital rendering (again no, that’s just a rendering). Once a phrase gets taken up by corporate marketing, it quickly spreads and its meaning becomes dispersed, tweaked and warped to suit each vendor’s agenda.

That said, the idea of the digital twin strikes me as a wholly valid one. We now have the ability to create rich, functional digital descriptions of the products that we are designing, representing not only the geometric shape and materials of the product, but its electronics, software, fluid and thermal performance, electromagnetic effects and much more.

Given all the money under the sun, it’s possible to have a physical product represented on a screen as if it were ‘real’, along with all of the data that has led us up to point. All of the requirements, the decisions, the workflows, the manufacturing and assembly processes could, theoretically, be simulated, defined and documented. If that’s technically feasible, then doesn’t it make sense to connect it up to the physical product once delivered? Of course. Having a doppelganger linked to the functional, real-world version is an incredibly powerful idea. When combined with simulation technologies, it could be possible to predict part failures or servicing requirements long before they actually happened.

Data on how the product is used could help to find problematic parts or subsystems. Fixes could be shipped and installed before the customer even knows an issue’s brewing. Then, when it comes to developing the next product, that rich set of real-world data could be taken and used as the input to refine and improve it.

For those who have been part of the design, engineering and manufacturing world and have tracked technology’s development, this may sound really familiar. It’s in part the original pitch for product lifecycle management (PLM): a means to capture all of the data created in your product’s development process and then its extended lifecycle. The digital twin idea is exactly this, too, but expanded to capture data from physical products.

Of course, as with PLM before it, there are very few organisations that have the need, the capability and, frankly, the budget to explore this concept fully. Those doing so were probably half-way there already, before someone in marketing gave it a nifty new name.

The problem is that to shoot for those customers, many of the software vendors like to put forth the idea that everyone should use the same approach, that they should open up the corporate coffers, just because its what ‘industry leaders’ do. The reality is very different. Products are not for the most part ‘smart’ and their manufacturing and assembly processes most certainly are not.

The reality is that, just as with PLM, organisations will take portions of the idea, appropriate for their products, best practices and workflows, and apply them in the context of company goals and budgets. While we do that, the tech vendors will continue to push the idea of the digital twin for a few more years and then move onto the next big thing that some company leader is willing to pay an expensive consulting firm to ‘verify’.

I’ve still no idea what the hell a ‘digital thread’ is, by the way – but I’m pretty sure it’s a lot less interesting than the smart sewing machine I’m eyeing up on Ebay.