Stage One was behind the Baku 2015 European Games opening ceremony which featured a giant flying pomegranate

Have you ever watched an opening ceremony for a major sporting event and wondered just how they pull it off? Take Baku 2015 the opening ceremony for the European Games in Azerbaijan’s capital in June 2015 featured a ‘cracked earth’ stage, complete with a 14 metre mountain rise up out of it, a 30m x 8m lake that magically appeared; a giant 10m flying pomegranate complete with over a thousand ‘seeds’ and a burning eclipse-effect cauldron with 30m arms.

It can only be described as breathtaking and was executed by Show Canada in conjunction with Stage One, a UK creative construction and manufacturing company.

As Stage One’s sales and marketing director Tim Leigh rather aptly puts it, “Behind every spectacular lies hours and hours of unspectacular preparation. Like feet furiously paddling underwater, this work is unseen and belied by the slick delivery above the surface.”

Most of these hours of preparation take place in Stage One’s 8,000m2 facility near York in Tockwith. Describing themselves as ‘makers’, the company designs, manufactures and constructs not only what the audience can see, often right down to the last component, but the means to achieve it too.

For instance, the above project featured over 20 lifts not to mention flying systems, hydraulics, hoists and winches and lighting components.

All of this is made within three hangars onsite laser tube cutter, a robotic welding arm and 3D printers. As acclaimed architect Thomas Heatherwick said a few years back when he extolled Stage One as being one of his favourite ‘makers’, “It’s a bit like a James Bond workshop – they’ve got the ability to make almost anything you can think of.”

Of course, most people (especially Brits) will remember Stage One’s project for Heatherwick: the London 2012 Olympic cauldron with its 204 individual copper petals that, once lit, rose together to form a single flame.

A vision that pushed the creative boundaries and kept Stage One’s workshops busy for five months including the design of a huge bespoke lift that had the capability of lifting the 16 tonne structure onto the stage surface from its concealed position beneath.

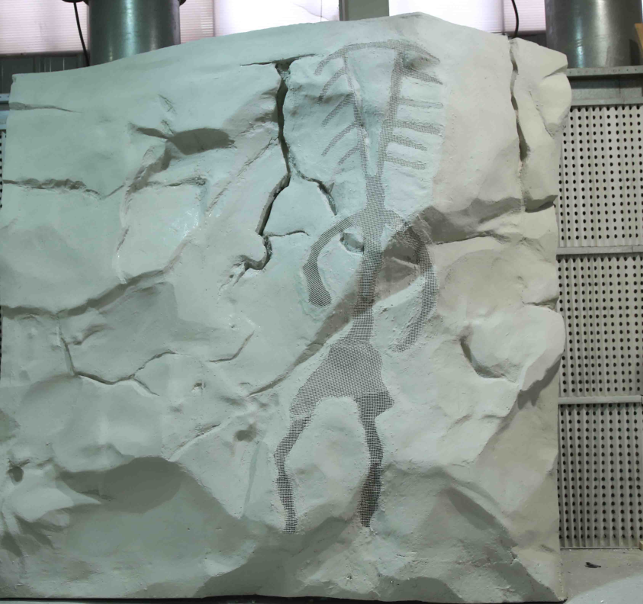

The Baku 2015 opening ceremony featured a ‘cracked earth’ stage that concealed 20 lifts to dramatically transform the stage into a 14m high mountain

Projects in all shapes and sizes

All size and manner of projects exit Stage One’s hangar doors whether they be for temporary architecture, stage set design, exhibition design, launch events, works of art, music festivals or theme parks… the list goes on.

“Some projects are very large and others rather small. We can pretty much build anything as long as there is time and enough budget and we’re not required to invert the laws of physics,” smiles Leigh.

The 10m pomegranate, which flew overhead during the ceremony, contained a thousand ‘seeds’

Most projects start with clients bringing Stage One a simple ‘napkin/back of an envelope’ sketch of their idea. These clients have either worked with them before, been recommended or who may have been to a traditional fabricator and the work has been too difficult to complete.

But as Leigh says, this doesn’t put them off. “We’re good at complex – sometimes we undertake projects without knowing at the start how on earth we’re going to achieve them. But that is what it means to be truly innovative.”

This does prove tricky when it comes to giving an estimate of how much a job will cost or how long it will take to complete. It will, however, in this initial stage try come up with a rough design that is reasonably well specified but won’t yet be drawn for manufacture.

“One of the challenges with innovation is we don’t have a catalogue of stuff. We are building everything from scratch so costing that is sometimes challenging” comments Leigh.

Stage One is also clear that it doesn’t want clients to merely view it as a factory in which a button is pressed at the start and after a time the completed project is spat out the other end. It wants very much to collaborate with clients right from the very early stages.

“For us this is the preferred route because it results in a rich interplay between exchanging ideas and means there is a shared ownership of the project as it gestates and takes on a life of its own,” says Leigh.

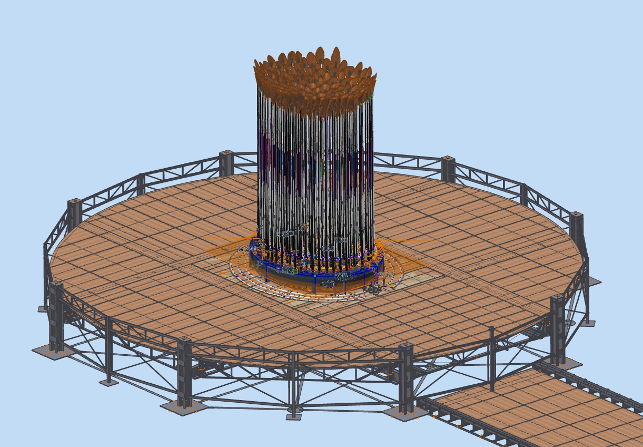

The stage being manufactured in Stage One’s workshops

Product development begins

Once given the go ahead, a project will then very quickly move into CAD where a team of 14 design engineers will take the client’s sketch and model it up in Autodesk Inventor. Here they’ll work out the most appropriate materials to use and the best processes to manufacture it. Essentially they are selecting the right tool for the job.

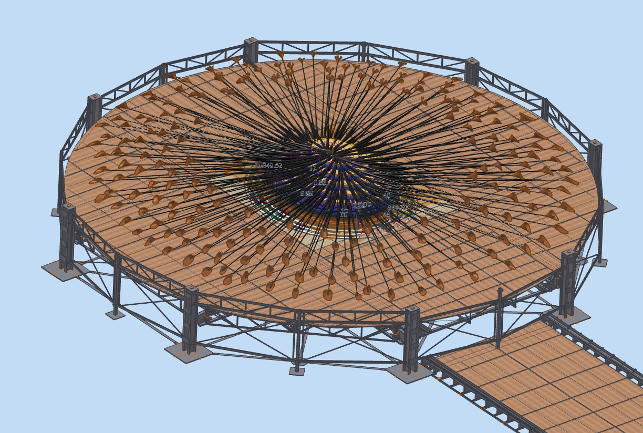

An Autodesk Inventor CAD model showing the London 2012 Olympic Cauldron lying flat

As one of the design engineers says, “There are so many ways to make something, it’s about picking the most efficient, appropriate and practical to build on site. And not forgetting the aesthetic too, of course.”

As in any product development project, prototyping is key at Stage One, even though some of the projects it creates are very large indeed. In this case, it will prototype a section to scale. “Whilst we build large scale stuff, a lot of the component pieces are repeats.

“We know that we are going to build 12,000 and if we know that we can do one well, we then know how long it is going to take and how it performs and then all we’ve got to do is rinse and repeat, as it were,” describes Leigh.

This was the case with the Serpentine Pavilion, which Stage One has worked on for the past eight years as main contractor. Last year the architect appointed for the temporary structure, which is exhibited in the grounds of London’s Serpentine Gallery during the summer, was Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG).

The ambitious design that features an ‘unzipped wall’ revealing a cavernous interior space is made from 1,900 open-ended glass fibre reinforced polymer boxes. In this case, Stage One’s designers concentrated on prototyping just one and once they knew how they would manufacture it, could then put the workshop to work on creating the other 1,899.

Prototyping is also important as it enables Stage One to experiment with different materials and explore with new technologies. And, of course, with prototyping being done literally in the hangar next door to the design office, it makes it very easy for the design engineer to go over and chat to the machinist or craftsman about what is needed and what can be achieved.

Then once lit all 204 petals rise up together to form one flame

Investing in technology

There is also an in-house 3D Printing Lab, which is used for prototyping and R&D work as well as the manufacture of final production parts.

The two 3D printers currently in use are the Stratasys Fortus 250mc with its 254 x 254 x 305 mm build envelope and the Fortus 900mc with its 914.4 x 609.6 x 914.4 mm build envelope.

The flat-bed laser cutter, one of many machines in Stage One’s vast workshops

“It’s tough knowing which technology horse to back. We researched quite heavily the various additive manufacturing technologies to buy into but we decided on an FDM [fused deposition modelling] machine in the end,” explains Leigh.

These machines are put to good use on a vast variety of projects and, as Leigh puts it, it’s not just about printing whimsical models. “3D printing of itself is not that interesting – anybody with enough money can go buy the right kit but actually when it does become interesting is for example when you combine 3D printing with 3D scanning.

“This means we can now create models of objects, print them on the 3D printer, scan them to collect the data and then scale them up on our CNC machines and all of a sudden you have a making capability that involves a whole different range of techniques.”

In fact, its Steinbichler Comet L3D scanner is often taken to site. For instance, it flew to Azerbaijan with one of Stage One’s mechanical design engineers to gather data for the manufacture of the mountain featured in the Baku 2015 opening ceremony mentioned earlier.

BIG’s 2016 Serpentine Pavilion comprised a 14m high wall of interlocking hollow bricks that peeled open into a cavernous space

Leigh admits that Stage One likes technology, which is obvious from its well-stocked workshops, and it is currently exploring adding significantly to its arsenal of 3D printing machines. “We’ve been experimenting with printing node connectors that will combine to create large scale structures but I can’t tell you too much about them as it’s our key to the future,” he smiles conspiratorially.

Manufacturing the creative vision

During the design and development process, once prototyping is complete and all the refinements and adjustments have been made, manufacturing can begin.

This is carried out alongside the creation of other requirements for a project such as lifts, hydraulics, cablenets, flying systems, lighting systems etc. including the software to operate them.

The structure was built using 1,900 GRP boxes, which were precisely orientated and stacked to within a 1mm tolerance of the footprint

Stage One will often then try to do a full scale test build before transporting all the various components of the project to site, wherever that may be in the world. This is a huge logistical endeavour for which it uses sophisticated tracking software. “This software details everything from what parts are on trucks to who should be on which aeroplane,” says Leigh.

As an example of what a huge undertaking this can be is The Hive that was created as the centre piece of the UK Pavilion at the 2015 World Expo in Milan in which Stage One was the main contractor. Here it collaborated with a project team, including the Nottingham-based artist Wolfgang Buttress, to bring the vision of a 17m high aluminium beehive sculpture to life.

The design featured 32 horizontal layers with each layer consisting of rods and cords of differing length to form a cuboid lattice with an internal spherical void 9m in diameter.

Each of its 169,300 components was modelled by the CAD team in Inventor and then manufactured in the workshops where they were inscribed with a reference number indicating its precise location within the structure. This included the creation of 30,000 nodes, which meant that no welding would need to be carried out during the assembly process, instead it could be bolted together and built up layer-by-layer as a kit of parts.

The Hive being assembled by the Stage One team at Kew Gardens

A team of twelve assembled the 50 tonne structure in Milan and thanks to carefully sequenced deliveries to site, this process was straightforward with the first layers of The Hive completed in January 2015 and the last just three months later.

Following the Expo and having been awarded a coveted gold award, the Stage One team had to then carefully disassemble the structure only to assemble it again at its new home in The Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, to open to the public in June 2016.

Driving away from these three hangars you can’t help being struck by the capability, scale and creativity of Stage One on a site quite literally off the beaten track. It is indeed, as Leigh puts it, “a really well kept secret.”

Creative manufacture on a grand scale at Stage One

Default