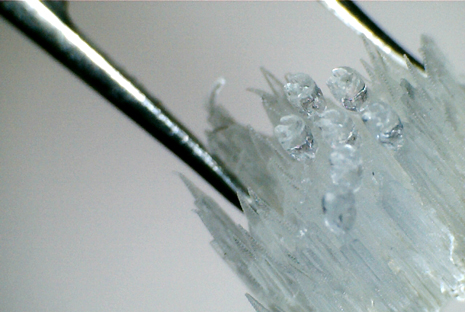

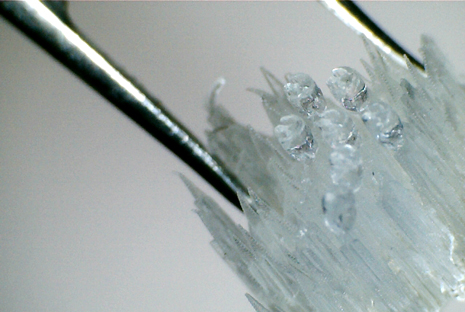

3D printed insect ears on SLA tips at 400x magnification. The tweezer in the shot gives an idea of dimensions

We’ve come across all manner of objects printed via 3D printing and now the Industrial Design Consultancy (IDC) has managed to produce 3D models of the smallest hearing organ known to science.

As part of pioneering research at the University of Bristol, IDC Models (the rapid prototyping and model making division of IDC) has pushed 3D printing to the limit in the development of life-size replicas of the katydid’s ears, using its high resolution Viper SLA machine.

The research project is focused on understanding how katydids actually hear as their ears, which are located in their legs, are up to 100 times smaller than the sound wave they are listening to.

Technically it shouldn’t be possible for them to hear at all, but researchers believe that sound diffraction could make hearing possible.

“3D printing is an amazing tool for science, particularly when researching structures. Before IDC’s models, I had to use a model that was about 1000 times bigger than the actual ear,” says Lydia France, a researcher at the University of Bristol.

“Another huge benefit of 3D printing is being able to alter structures. For example, I could investigate how a flap works on the ear by having a model with it present, and with it removed. If I was using a real life sample, this would be next to impossible to do without very steady hands and a lot of trial and error!”

According to France, the models of IDC’s insect ears are supporting just one of several research projects studying the physics behind hearing. By having a better understanding of alternative hearing methods such as this, research will be able to advance the technology of human hearing aids in the future.