A leading and historic producer of ceramic tiles, Craven Dunnill Jackfield is using new technologies to boost production without compromising on its long-held traditions, as Claudia Schergna reports

Stepping off the train in Jackfield is akin to arriving at an open-air museum dedicated to the history of the Industrial Revolution in the UK.

Everything in this Shropshire town is a red-brick shrine to enterprise and industry, from its railway, the second built in the whole of the UK in order to connect the coal mines of the Black Country to its factories, to the nearby Iron Bridge, spanning the River Severn and the first anywhere in the world to be made from cast iron.

Here in Jackfield, one industry prevailed over all others: pottery. To this day, the village is still home to Craven Dunnill Jackfield, one of the most prestigious tile producers and manufacturers worldwide. Contemporary projects for the firm include ambitious restorations at the Houses of Parliament in London, as well as its Australian equivalent on the other side of the world.

Other work include decorations seen at Harrods Food Halls and at over 60 London Underground stations. The latter includes the new, super-Instagrammable interlocking triangles embedded with LED lights that are located in the new pedestrian tunnel at King’s Cross Station.

Craven Dunnill Jackfield is still located in its original building, erected in 1874. But today, that building also home to a museum, where visitors can immerse themselves in early twentieth-century manufacturing history and learn about traditional tile-making processes that are still being used by employees working just a few metres away.

Behind closed doors

Factory manager Gemma Ball and commercial director Richard Butler lead the way to the first of two main areas in the factory: the Encaustic Department. Here, tiles are produced by skilled artisans who carve and glaze them by hand before they make their onward journey, primarily to restoration projects.

The next stop on the tour is the Wall Tile Department. It’s a name that the company has long since outgrown, explains Gemma Ball. “Pretty much what we do here is not tile-related,” she explains. “It got bigger and bigger and more architectural as we’ve grown up.”

In this building, we also find the large kilns where tiles and architectural components are fired before being glazed.

The colouring service is still very much done via traditional techniques: “Ninety percent are hand-dipp in the glaze after the pieces are fired,” explains Ball, her voice overlapping with the ticking of a metronome in the background. This helps employees ensure the tiles get dipped into the glaze for the correct period of time.

In the next room, Tim Perks is working. He’s an industry veteran who has nonetheless only recently joined Craven Dunnill Jackfield. Ceramic modelling is a dying art, he explains, due to technological developments, and because of a lack of funding for art colleges.

He doesn’t feel like his job is threatened by technology, however. Quite the opposite, in fact: “I believe in a marriage of the two,” he says. “The technology, it’s been an eye-opener for me.” That said, he still believes in handfinishing for some items, he adds, “because it gives a nuanced, sort of organic quality.”

Perks works in close contact with Jed Hammerman, the man behind Craven Dunnill Jackfield’s technological innovations. Hammerman first joined the company via the Knowledge Transfer Partnership, a graduate scheme that aims to connect graduates and businesses. The aim here is mutual benefit, with graduates gaining professional qualifications and businesses learning to incorporate new technology into their workflows.

While Hammerman had never worked with ceramics before, his degree in 3D design has proved to be extremely valuable at Craven Dunnill Jackfield, which was looking for ways to boost production while maintaining the quality of its hand-crafted tiles.

“When I first started, this room was empty,” says Hammerman, looking out at the dozens of models that now populate it, along with a large CNC machine and an Artec Spider 3D scanner.

A successful marriage

The introduction of new technology into the workflows of a company that has been employing traditional methods for centuries might have raised concerns for workers and customers. Instead, Craven Dunnill Jackfield stands as a glorious example of what happens when you successfully marry technology and craft, modernity and tradition.

“Rather than replacing any of the hand carvers, my job is to take some of the workload off them,” explains Hammerman. “Rather than starting from scratch, I give them a mostly finished piece and they provide those final little details that the computer can’t quite do.”

Were people ever worried about robots (and technology in general) taking over their jobs? “That never happened,” he says firmly. “It was always a mix of the two. Now we can do the same stuff, but faster and for more clients.”

The first piece of equipment that Hammerman introduced was the 3D scanner. This turned out to be particularly convenient for restoration projects. Previously, clients were forced to rip tiles off walls and send them to the factory to be restored. Now, the team can visit the site in person and scan those tiles that need restoring.

For this purpose, the team selected the Artec Spider 3D, a handheld scanner that can be easily transported and manoeuvred on scaffolding, while providing high resolution and accuracy.

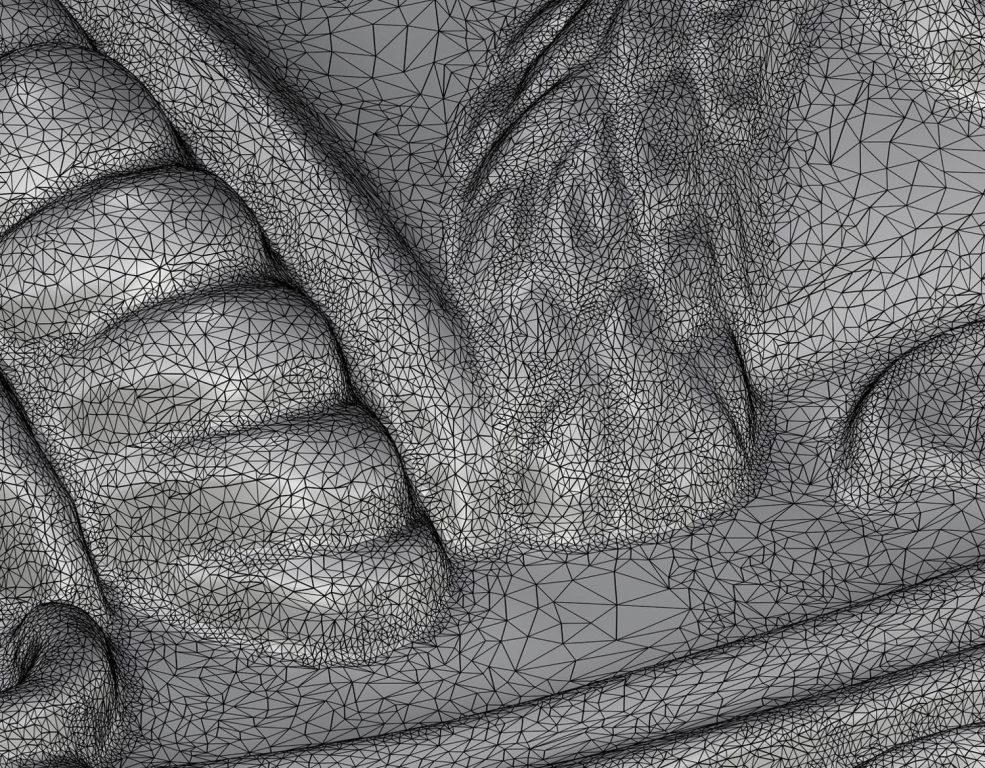

Once tiles have been captured and appear in the Artec Studio software, they are imported into CAD for a design phase that uses Rhino. At this stage, the project is passed to a modeller, who will intervene manually to create the initial mould, using the organic lines typical of handmade production.

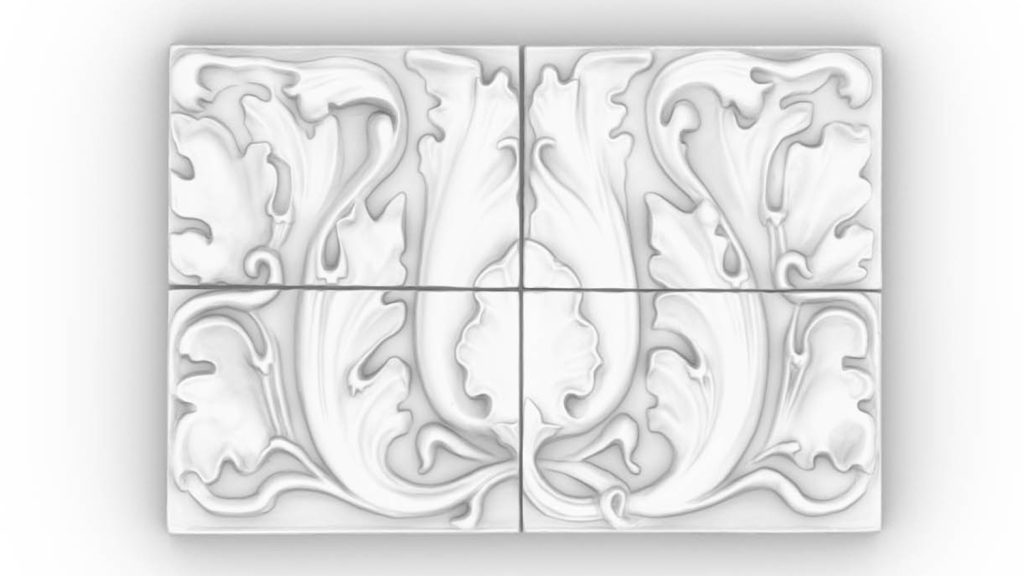

Creating moulds this way is much faster. A mould maker only needs to create half of the mould, which is then 3D scanned and mirrored in CAD. Using Rhino, Hammerman adds sides to the original shape in order to create a solid block suitable for CNC milling and then finally inverts it.

The CAM programming software Mayka V8 is used to create toolpaths for the CNC mill, which offers a couple of key advantages. First, jobs can be completed overnight, as there is no need for workers to supervise the machine. Second, it allows the team to produce everything inhouse, instead of commissioning external mould makers.

This has helped grow the company’s relationships with clients enormously: “Now we can just fire across five new designs in an hour, giving the customer a lot of options to choose from,” says Hammerman. “We can change shapes and colours as they wish.”

Craven Dunnill Jackfield // Guarding trade secrets

While 2D tiles are now very easy to replicate thanks to these technologies, when it comes to 3D tiles, the process is not so straightforward.

The glazing on the tiles makes them extremely hard to scan. When light gets reflected by glaze into the scanner, it’s unable to register the data.

“This was the issue when I went around trade shows,” Hammerman recalls of the time he spent scouting for the most suitable 3D scanner: “I would bring a tile with me and ask: ‘Can you scan that?’, and everyone would be like, ‘Can’t do it, sorry, bye!’”

Most 3D scanner manufacturers recommend using a scanning spray on shiny surfaces to give them a matte finish, but Hammerman found that, even using the spray, he couldn’t determine the depth of the hand-carved channels in the tile.

Solving this problem became Hammerman’s prime mission at Craven Dunnill Jackfield. “The magic of the Knowledge Transfer Partnership project, what came out of it, was finding a way for us to determine what the surface underneath the glaze was like,” he says.

To solve the issue, and after extensive research conducted at both Craven Dunnill Jackfield and at the University of West England where Hammerman was previously doing research as part of the Knowledge Transfer Partnership scheme, he created a programme in Rhino to determine the topography of the underlying surface. “If you were to look into a pool of water, you would see the dark bit in the middle and the light bits of the side,” he explains.

“For example, for all the black bits, we work out that’s 0.5 millimetres deep, and same with the other 100 colours in there,” he continues, pointing at a very colourful tile design on the screen in front of us.

The scanner picks up all the pinpoints of light as they are refracted off the tile back into one of its lenses. The way the Artec Spider works is that one of the lenses projects a light into the object, while the other picks up where the light bounces off.

“What I was able to do was turn the 3D model into a format that allowed me to manipulate the surface in an unconventional way. Then I wrote a programme to move them automatically, based on their colour,” he says. “I realised that each colour produces a slightly different result. You end up with a dataset that describes how the light reacts with the glaze.”

The software that Hammerman developed to show this graph is so innovative in the industry that Craven Dunnill Jackfield is keeping it a closely held trade secret.

Working with 3D scanning and producing the moulds with a CNC machine also reduces the margin of error that results when producing pieces entirely by hand. In this way, significant time and material waste are saved.

“After I’ve redesigned something, we can just cast it and we know it’s going to be right. No one has to measure anything. No one has to even look at it,” says Hammerman, picking up a small rectangular tile.

“This would have originally been made by having some rubber casting applied to them, then lining them up by eye, maybe putting something in between each one to have a regular gap,” he says.

Producing cast tiles by hand in this way would often result in slight wobbles in the tiles, making their assembly particularly challenging.

New life for British landmarks

The introduction of these technologies coincided with a project commissioned by an extremely prestigious client: Harrods. The Grade II-listed Food Halls inside London’s most famous department store are covered in decorative tiles and Craven Dunnill Jackfield was commissioned to restore this environment.

Hammerman describes this first application of his newly developed technology as a semi-success: “It worked, but not quite how I envisioned it would work. We didn’t know what was going to happen.”

The Harrods project was carried out with a mix of traditional techniques and newly introduced technologies. “That was the first point of learning. We realised we can’t just replace hand carving. It is essential. It’s part of what makes it work.”

A lot has changed since then. A more recent project has been the recreation of The Elephant and Castle pub, commissioned by the Black Country Living Museum.

The original pub, which stood on the corner of Stafford Street and Cannock Road in Wolverhampton, was illegally demolished in 2001. Hammerman didn’t have many references with which he could work, just a small fragment of tile that he shows us, saying: “This was one of the few pieces that survived. Someone just found it in the rubble and happened to take it with them.”

The 3D model he produced in Rhino was entirely based on a handful of original pieces of the façade that remained following the demolition, plus a handful of old photographs. With the help of colleague Michelle Cox, the production glaze technician who oversees the company’s colour-matching service, he recreated the whole building, with its wall tiles, faience and decorative gold lettering.

Craven Dunnill Jackfield // Creating a database

Technology is often perceived to be the enemy of traditional craft. In the case of Craven Dunnill Jackfield, it is enabling traditional methods not only to survive, but also get passed on to future generations.

Moulds, for example, were previously created by hand by artisans. With production levels being so high, they would often make a single mould for each project. In short, there were no spares.

Hammerman shows us a very heavy dust press mould that he is currently restoring: “This is probably older than either of us,” he jokes. “It’s warping, the corners are moving down. God knows how many presses it’s undergone. Tens of thousands, probably. And there’s no back-up.”

For that specific tile, he had to scan the mould and redesign it from scratch on Rhino. As a result, he can now be sure that, if it breaks or gets damaged again, the project is saved on a hard drive and can be milled as many times as needed.

“We can make another one without having to worry, and we know it’s going to be exactly the same. That’s opposed to someone taking the rubber or the plaster off that, and then making a resin off of it, with all that shrinkage and movement that comes with it, which is possibly how it ended up warped in the first place,” he says.

By building this database and adding digital technologies to the workflow, Craven Dunnill Jackfield has been able to scale its business, shifting from being a symbol of the first industrial revolution to embracing the technologies that are defining the fourth.